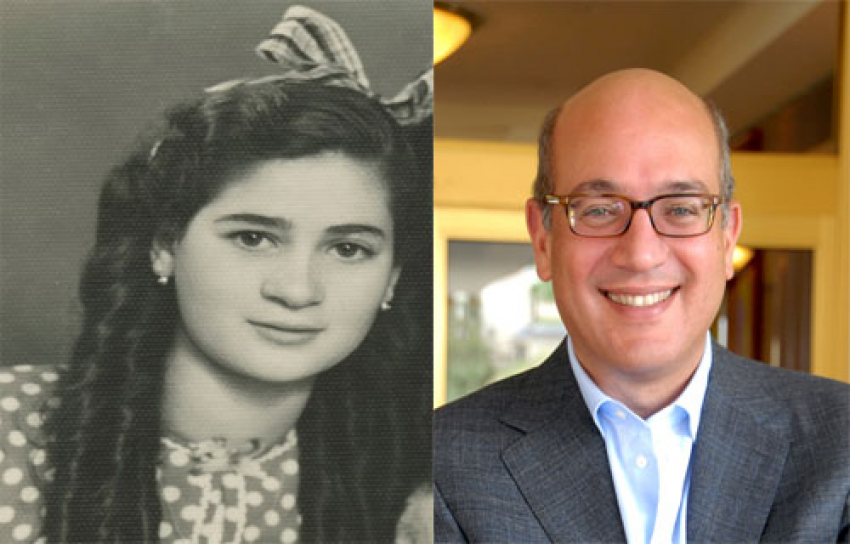

Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh studied history, photography and visual anthropology in Paris. From 2006 to 2011, she lived in Burj al-Shamali, a Palestinian refugee camp near Sour (Tyre) in south Lebanon, where she carried out photographic research including a dialogical project with a group of young Palestinians and archival work on family and studio photographs. Since 2008, Yasmine Eid-Sabbagh has been a member of the Arab Image Foundation (www.fai.org.lb). She is also a doctoral candidate at the Academy of Fine Arts in Vienna.

During an artist’s residency at the Palestinian Museum in Ramallah in autumn 2014, she shared her experience working in Burj al-Shamali with the Museum staff, thus making a valuable contribution to their work on the Museum’s opening exhibition (Never Part, planned for 2016). She also collaborated on the curation of the exhibition Introducing Palestine’s Museums, which was part of the second Qalandiya International biennial.

Omar al-Qattan, meanwhile, is chairman of the A. M. Qattan Foundation and the Palestinian Museum Task Force. Since 1991, he has also worked as a film producer and director. In 2005, he became vice-chair of Al-Hani Construction and Contracting, his family’s business in Kuwait, which supports a large part of the Foundation’s work.

The Palestinian Museum is a project of the Welfare Association.

The interview:

YES: What I would like to understand, actually, is your perspective on these different cultural initiatives that are going on now in Palestine - because from what I can observe, you have become a kind of spokesman for culture there, haven’t you?

OAQ: I wouldn’t say that - I think it might be misinterpreted!

YES: No, I know, but it is something that interests me, this tension of you actually, by doing things, and by your family initiating things and also being part of the Welfare Association, have become – I’m not saying you’re claiming yourself as such – but...

OAQ: You know, the beauty of how culture works - and I mean culture in the widest sense, not just the visual arts, music, literature etc. but the things that we share – culture in that sense has a cumulative power, so that one thing leads to another very quickly. It spreads like wildfire. The thing is, though, you have to start the fire – a constructive fire, not a destructive fire – and then other people join in and these things build up momentum, almost in an uncoordinated way. And so on!

Of course, there’s also a lot of risk and naivety involved in starting something new, so for example I remember that when we launched the Qattan Foundation’s Culture and Arts programme in 1999, few people really understood what we were doing...

YES: What about the cultural work that had been done by the Welfare Association and other organisations before then?

OAQ: The Welfare Association is a very different organisation. First of all, it’s a membership organisation with a lot of different people and different views, even more so now, and the first generation – many of whom had experienced the Nakba - had a very conventional understanding of cultural development. Their interventions were chiefly focused on what they termed identity conservation and preservation of the patrimony (al hifathu ala al turath), and so on. So in a way it was a very conservative concept, and also very nationalist and patrician. I joined the Association in the late ‘90s and when the Palestinian Museum project was first mooted, its most passionate proponent was the late Professor Ibrahim Abu-Lughod, who was set on building a memorial museum; I actually resigned from the committee because I couldn’t get on board with this concept. A year later, the second Intifada erupted, so the project was put to bed for a few years. My concern then, as now, was that Palestinian social and political reality is anyway very dispersed, very horizontal, and from around the year 2000 it has begun to be violently fragmented by the Israeli occupation forces, its isolation of Jerusalem and Gaza, the hundreds of checkpoints, the brutalisation of Palestinian citizens in Israel etc. People from different parts of Palestine were not able to meet, let alone work together – including of course artists and writers. The very social fabric of our society was being violated and torn apart. That’s why I came up with the idea of modelling the Palestinian Museum as a centralised hub that could reach anywhere, with satellites that could be everywhere!

That’s also when I started thinking about having a thematic museum rather than one built to house a collection. The reason for this is that our patrimony is so fragile and so threatened that in order to protect it, we cannot simply collect and preserve it (and even that process is fraught with risk, of Israeli confiscation etc.) but we also need to give it life through an ambitious programme of engagement with contemporary audiences which would allow them to reflect upon, explore, discover and debate themes of Palestinian history and culture. This is what is meant by a thematic museum.

YES: But this is a political stance, if I understand you properly, because I guess in this sense the Museum somehow ideally contributes to state building?

OAQ: I don’t think it in that sense directly. I think it contributes to sumud or steadfastness – I hope it will – in the sense that it mobilises people around projects they can defend and which can sustain them in their homeland. If I go back to the early days of the Qattan Foundation’s cultural programme, we knew then that our resources were limited, both as a family and as a society, because the cultural skillset was weak. Not many people were working in these fields. So, we took a proactive and a catalysing role. That’s why we chose to use the model of competitions, of activities that can encourage people to work together. At the time, our budget was tiny and nobody thought that it was going to work - except that it was attractive, it involved young people, the strategies were clear. Soon others started to see the value of this alternative sector that had been neglected for long, or had been only exercised under the auspices of the PLO. People started realising that actually the PLO was disintegrating as a result of the failures of Oslo, but also that this should not mean that we don’t carry on with our cultural life and indeed actively contribute to a new political project (that this has not happened is one of the most pressing challenges the Palestinian people face today).

So the Qattan Culture and Arts Programme grew from an initial budget of $70,000 in 1999, which is nothing for a small town, let alone a whole country, to about twelve or thirteen times that today. And while we were happy to get help and resources from other organisations, the most vital support was not financial - it was the belief that people started having in what we were doing. When I say that, I mean that for instance more young people began pursuing artistic disciplines: Palestinian culture became perhaps our most potent and effective ambassador and we saw culture brought people together (in some cases, for the first time in decades) from all parts of historic Palestine. So more and more people began to appreciate the fundamental value of the whole cultural sector.

Of course, one has to also recognise that during the last decade, Palestinian society has become culturally much more inward looking and conservative and there is not doubt a growing danger of a disconnect between the cultural sector and society as a whole. Only two days ago, when we were in Jerusalem on this amazing cultural tour of the Old City of Jerusalem as part of Qalandiya International Biennial and the Jerusalem Show, a fourteen-year-old was being shot by the Israeli forces a kilometre away. At the same time, I know that a dynamic, open and creative culture can only strengthen our presence on our land and indeed the bonds between our scattered communities.

YES: I can see, and I have also had the chance to experience, these different dynamisms that you’re talking about and I think they’re really interesting. For example I’ve been very positively surprised by the Qattan Young Artist of the Year (YAYA) exhibition[1] this year, which is really impressive. It is so intelligent to have had the competition evolve into a process in which the young artists are involved. I can imagine these young people really profiting from the exchange with the jury and with each other and from the process, rather than just getting a certain amount of money if they win.

OAQ: Absolutely.

YES: So now when I look at the Museum project, one thing that surprises me and that I want to ask you about, perhaps a bit provokingly, is this very big building that threatens to become a sort of monument. I wonder, is this also a way to place the project somewhere in this, I don’t know, call it cultural authority void? Otherwise why this impressive building...?

QAQ: You know it’s really interesting you ask me this because... have you visited Gaza?

YES: No.

OAQ: Okay so, in Gaza, the Qattan Foundation runs a children’s cultural centre[2].

YES: Yes, I’ve heard about it.

OAQ: This was one of our first projects in the late ‘90s. We were developing the concept for the centre at almost the same time as the debate was going on within Welfare Association about what kind of Palestinian Museum we wanted to build. My own preference for the Qattan centre was to create exactly the same model as the one I had proposed for the museum, in other words to have a main (but not necessarily large) hub with many satellites scattered all over the Gaza Strip and hopefully all over Palestine, forming a network of expertise that would share resources and would be very accessible for children so they wouldn’t have to physically travel to the main centre/hub. Now, I was not able to prevail over everybody involved. My father in particular argued that people actually need to see something very big, literally very concrete, in order to believe in it. So I was persuaded that it was perhaps too premature to think of my model, and I accepted his argument. Now, in a way both models have been applied to the Museum: we have a hub, which people can see and believe in, but also many satellites as well. And as for its size – it may be big for Palestine but not for a world-class museum, which is what we want to create!

YES: But if you look at it as something that is part of an ongoing, let’s say, movement of all these museums coming up in Palestine, you have the Mahmoud Darwish museum, the Arafat museum, and all of them are really quite imposing. I mean, they’re big buildings that just scream visibility, don’t you think? It makes one think of a race for monuments – even for power. So I wonder, how do you position yourself in such a context?

OAQ: I understand the anxiety about that. I had a similar anxiety about the Centre for the Child in Gaza when it was being built. But you know, in the end if it’s used and enjoyed by a lot of people, and if it makes a very sustained effort to go out to communities with an effective outreach programme, as indeed it did, and eventually to create satellites, then so what if it is “big” and visible. People in Gaza now speak of the centre as a landmark, something they own and are proud of. In recent years we also have a partnership with a centre in Maghazi, a grassroots centre that is run by the community, and there are other partnerships too. There’s now going to be a similar centre in Jenin in the West Bank as well, so that networking dynamism, if you like, which is decentralising, democratic and horizontal, is very much part of our work. At the same time, yes - people do need these symbolic buildings. The difference between our museum and the Arafat or Mahmoud Darwish museums is that we’re not attached to a political power. Of course, I know that the Welfare Association is powerful economically, or individual members of the Association certainly are, but because of the way it has been conceived, I don’t think the Palestinian Museum is going to be imposing a specific agenda or ideology. This decentralised model of a mother ship that I talked about is going to be the most vital part of the Museum’s identity. You can see that from the exhibition you worked on[3], which was a very clear effort to reach out to all the other museums operating Palestine and to be inclusive without being centralising.

YES: Well, yes and no... I have heard lots of feedback in which people have a problem with the Museum already placing itself as the “mother museum” embracing all these other smaller museums, many of which have already existed for years. This seemed problematic to many people, which is understandable, right?

OAQ: Sure.

YES: I could hear from some comments that there is animosity to this and somehow that this building also symbolises a kind of authority over other already-existing cultural projects, be they museums or personal collections or whatever else.

OAQ: The best way to address this concern is to say that the Museum is going to be as good as its projects. If what it does is not interesting, then please slam it! But I can assure you that it’s not there to be a source of authority.

YES: I was interested to hear what your position is towards this. I can see this being a question one has to be conscious of while working on the museum project... I’m not necessarily accusing the PM of anything.

OAQ: No, of course. And in the absence of proper, sovereign authority, people are not only sensitive to people who may have no legitimacy – which is absolutely right – but, paradoxically, they also impulsively want to fill the gaps left by that absence. So for example, from the very beginning everybody wanted the museum to be in Jerusalem. Of course we were faced with the reality that we can’t put it in Jerusalem: firstly, Israelis would not have let us, and secondly, a lot of Palestinians could not and still can’t get to Jerusalem. We were never going to be able to do it there in the circumstances. Hence the model I described - which may be a little bit hollow because the reality is so overwhelmingly against us and the balance of power so much against Palestinian society. Yet this “ruse” of having the Museum in Birzeit, near a university, not in the most obvious place, not in the capital city, not even in the temporary capital, Ramallah - I think that needs to work in its favour as a “horizontal” democratic institution. Now, if in the beginning that means that it will rattle some people or it will feel like it’s a source of “authority” people will have to judge it on the merits of its programmes. Nobody is forcing anybody to do anything: if smaller museums don’t want to be part of a larger network, it is their choice. But I don’t think we should use that as an excuse not to do our work as a mobilising institution.

YES: On the contrary, I agree with you, I’m always thinking that in fact this concept of which you are talking which is the hub with several satellites, is what is most interesting about the project. I would accentuate it - I can imagine all of these different types of discrete but very concrete and sustained enduring actions here and there being very convincing. I guess, in a way, I would encourage the concentration to be on the programmes and exhibitions that are happening in the satellites. I mean that I think they should attract the greater attention, rather than the building itself. I guess that one of the problems in this particular moment is that attention is turned towards this building site where something is being created.

OAQ: Well, it’s going to be a beautiful building!

YES: I’m sure. But I, for example, have doubts about the idea of a finished building with a nice opening exhibition in it. This would be so self-celebrating. I hope the museum will be able to have a critical position towards the building, its role and its monumentality.

OAQ: I will give you another, though different, example of the power of horizontal cultural collaboration, namely the Palestinian Performing Arts Network. The dynamic of this network is that a few years ago a lot of different performing arts institutions and groups working in music, theatre, dance etc. were not pulling their resources together efficiently, and some people, including our staff, were calling for the creation of a network. That was an interesting process because it began with fragmentary groups and ended up as one network, which we now manage and which has been able to marshal a lot of professional and financial support. Now you could say that that gives the Qattan Foundation a lot of power, but the process through which it was developed was very democratic, and it’s still run very democratically. My view, though, is that whatever happens, at some point in any project, you need a centralised point of leadership, whether intellectual or financial. That’s why it’s very important that when we do critique the centralisation of some of the cultural life of Palestine in Ramallah, we mustn’t forget that without the city, in the modern, civic sense of the word, there is no cultural development. We need centres, even if they are temporary.

YES: You said before that you were not initially persuaded by the proposal that your father made for the children’s centre in Gaza – i.e. for a highly visible landmark that people could see and believe in. I had the impression that you maybe believed in something else. So what do you think? What are the possibilities and difficulties of greater “discretion” in the context of cultural work? Do you think that discretion can also be effective? I sometimes wonder about this, for example, when I think of my personal experience in Burj el-Shamali refugee camp in Lebanon where I worked for 10 years. There I always observed how the different NGOs and local associations would compete about who had the biggest buildings, the biggest programmes. They were constantly rushing to engage 200 kids rather than 10. I myself struggled for several years before I could negotiate to occupy a small space in which I could meet with the young people I was working with, and in which I could work on digitising the collections people would entrust me with. One of the problems was that people would say I was not engaging a big enough number of people in my work. But for me time and presence was what was most important: I preferred working discretely but concretely with the different individuals I had engaged with.

OAQ: We absolutely need to nurture these discrete initiatives - I mean, without them there is no bigger project. The challenge is how to find the individuals and groups doing or wanting to undertake their own initiatives, how to bring them out of the woodwork. Public competitions are very effective at doing that. And the Qattan Foundation’s cultural programme has been quite successful in this area. To be able to mobilise, you do need to be able to identify and invest in a lot of small initiatives.

YES: And this is actually the point I want to get to. So what I wonder sometimes is, if you took the effort and all the energy and time and even money that is put into building the symbolic, and saw how far that might go if you concentrated on discretion and on this very concrete action and on smaller projects etc., would the symbolic then still be necessary?

OAQ: You should be doing both things at once – investing in the discreet/horizontal/organic, of course, but also in the symbolic/monumental/concrete. Cultural anthropology and history tell us about both needs and the dialectical tension between them is fascinating. The only thing I would add is that you can’t build without thinking first about a process. Not just the use of the spaces and how you’re going to use those, but how the building is going to relate to the rest of its surroundings. We did that very thoroughly. If you look at the strategic plan for the Museum, you find that although it’s not as clearly spelled out as I may have spelled it out here, it’s very much in our literature that we are a transnational organisation, that we will reach out to Palestinians wherever they are within historic Palestine and to the Palestinian diaspora wherever it exists. For example, we’ve already done research in Chile and one of the Museum’s opening shows will be in Beirut. This horizontal dynamic is absolutely part of the Museum’s strategy - it’s not something that we thought about later. Similarly with the Qattan Gaza centre, the outreach dimension was conceived during planning, so provisions for it were made early. Today we also benefit from very exciting virtual and online technologies which give entirely new dimensions to the concept of outreach, and of course the Museum’s online platform is considered as a central part of its programming rather than just a marketing or communications tool.

I should also mention that the Museum has grander ambitions still. The current building, due to open in 2016, represents only phase one. Phase two has already been designed, and the only reason we’re not building it is that we don’t currently have the funding in place. So if you think the current building will be big, it’s going to be even bigger in future! (Laughs).

YES: I know, but it’s something that I would keep questioning. It’s an issue of visibility, isn’t it?

OAQ: Can you clarify that?

YES: Couldn’t it be argued that this big building might finally also make the smaller, discrete actions that you are describing somehow invisible? How far are you annihilating your own work? I think it’s important to think and rethink these questions. There’s always the possibility of drifting in one direction that then becomes an annihilating force on the rest of what you’re doing. I think it is theoretically easy to say one has to do both at the same time, but in fact it is very difficult to live up to this theory.

OAQ: Let’s talk a little bit about the Qattan Foundation’s own new building, which is also big. It’ll be bigger than the Museum, in fact, and will also open in 2016. At the moment, we’re going through our five year planning process, as I was explaining to you, and one of my biggest anxieties is that we risk turning into a sort of stultified bureaucracy, with people running out of ideas, repeating what they’re doing, not being able to develop nor innovate and so on, while at the same time working in a magnificent new building. Currently, the Foundation works on two main tracks (culture and education) in four different places – West Bank and the areas of Palestine occupied in 1948, Gaza, Lebanon and the UK. For years, we have managed to develop quite an efficient but decentralised structure, something we still feel is a great strength. At the same time, while we may be relatively decentralised, the two main tracks – and of course those who lead them, including of course myself - are very dominant as far as the content of programmes is concerned. This in many ways a strength, since it leads to coherence, but it also means that we run the risk of becoming a repetitive bureaucracy rather than the inspiring, creative institution we all aspire to. We have also been frustrated that the current structure does not encourage collaboration between the Foundation’s main tracks and programmes.

So I proposed a different organisational model that we are currently exploring whereby we replace the old “hierarchy” with a core circle, representing our core services – the public spaces, the equipment banks, administration and finance and technical support - and then connected to this core circle would be other smaller circles that represent different existing and future initiatives. This could also mean that people could approach us with their ‘discrete projects’ as you called them, and these would latch onto this core circle (and overlap with other existing programmes/circles). And discreet projects/circles would detach from this structure once they were finished, almost as a constellation of stars might do!

Now that’s all very lovely and theoretical, so we are still thinking of what it might mean in practice; the key point, though, is that the Foundation become much more akin to an experimental hub. I don’t mean experimental in the sense of haphazard, but meaning a space that can welcome people to come with their discrete projects and then leave again without feeling that we are a source of “authority” but rather a source of inspiration and a space for innovation and interaction, which is welcoming, but at the same time expects you to use it as a launch pad rather than a place to sit and become complacent and run out of ideas. Let me be clear though: as we develop this concept, the current work being done at the Foundation will not be affected, and as I hope you know there’s a lot of really good work going on there.

YES: Absolutely, and I guess there’s something that is crucial in its work, which is that its catalyst is generosity, which already gives it a very interesting and important starting point.

OAQ: Yes, though that too is problematic in that we are an essentially archaic, patrician society that is rapidly changing, so we need to change too. For instance, until now the Foundation was centred on one man, my father: that is no longer possible, notwithstanding his huge importance to it. He would be the first person to insist on renewal and change in line with the needs of the age. Firstly, none of us will be around forever. Secondly, society itself is changing. So the old model of the patrician, generous philanthropist is not going to hold up anymore. What we need to do is to develop an alternative model. And I believe this applies to society as a whole. It is no longer adequate for people to wait for others to be generous, be that other foundations or individuals. They themselves must apply the same spirit elsewhere, and create what you call discrete projects which are social, which are collective, which are viable and which then become larger than the sum of their individual parts. We as a foundation also need to develop sustainable projects that don’t need to depend on us.

On a small scale, this is already happening: for example, the first director of the Centre for the Child left us two years ago after fourteen years of relentless and exhausting service. She then went for a sabbatical to France, and came back to start her own nursery school in Deir al-Balah, which is where she comes from in the Gaza Strip, using local resources and some support from outside. So that’s the kind of thing I would like to see everybody do with the Foundation: use the resources of the Foundation and then launch their own independent project somewhere else. The last point I’d make, just to go back to this idea of generosity, is that we think that what we’re doing is valuable for everybody and therefore everybody should, in some way, contribute to it. In communities which are very, very poor, of course we don’t expect people to pay for services, but there is no reason why they cannot volunteer, and in communities where we know that people are already paying for KGs or spending money on things which they might better spare to spend on services for their own children or schools or their local cultural life, we believe that they should take ownership of initiatives and contribute to them. If you take that model to an even higher level, I’ve always hoped that the day would come when we as a foundation would become redundant and that there would be a system of taxation and a democratic and adequate allocation of resources to culture and education, which would make us superfluous. At which point we would just go and do something else!

YES: But where do you project this? Do you project this on this society with this authority?

OAQ: Why not? We have to get to a point where we break the old up-down model of charitable giving... I feel the old order is collapsing. We haven’t got a new order. The old collective, oppressive order, which is very tribal, is falling apart. But we haven’t yet got something that works as a real alternative. I think that’s true of the whole Arab world, so why can’t we as a progressive foundation be part of that discussion about the future? Indeed we must!

YES: You should not only be part of this discussion, you should ideally be the self-critical exemplary of it.

OAQ: We have to offer models. Why not think that it’s possible for us to become a society where the collective project is recognised and supported by everybody? Where we would have a different, fearless relationship with authority and run our own affairs freely and without interference from “above”? What is the point of self-determination and autonomy, otherwise?

YES: Absolutely. I’m surprised you say that because it seems very idealistic or, let’s say...

OAQ: I’m very utopian!

YES: (Laughs). Utopian, that’s the right word...

OAQ: Otherwise how can you think through the mess? I really don’t know. But we’ll get there I think. Maybe not our generation, maybe the next, or the one after that.

YES: I think it’s a great challenge to hold on to such a vision. You have to hold onto utopian ideas in order to move on. I think otherwise I also would not have gotten anywhere in the camp for five years working with these young people, even on such a small scale.

OAQ: But you probably had an equally difficult challenge.

YES: I’d say the challenge was similar. It was difficult to live up to the proposition of critical and radical pedagogy that I proposed as a tool for collaboration and research. Of course people where suspicious about me, about my research and my interest in their relation to photographs. It took lots of time for people to recognize the meaning of thinking about the existence of their photographs. And as I said before, I think it was time and presence that allowed a process to unfold. And finally I think it is exactly this process that allowed many different perspectives for everyone involved.

But to wrap up: this utopian idea, and the fact that recently I’ve seen you speaking at the opening of Qalandiya International (biennial), and also at the Museum’s exhibition and other public events, these things take us back to what I said at the beginning of this conversation. I think you have this position of being one of the spokespersons for Palestinian culture. How do you see this position evolving - what do you ask yourself in this position? What is it that you’re aiming for?

OAQ: Well, I started out as a filmmaker. I never ever call myself an artist, although in today’s terminology I’m probably a retired one! I have a passion for this and I’m very envious of artists because of the freedom they have to do what the hell they want. (Laughs).

YES: But this is what you’re doing!

OAQ: Well, it isn’t really - I have these huge responsibilities, including our family business, which partly funds the Foundation. I don’t enjoy the kind of freedom I was describing, and I’m very envious of people who do. And I’m happy for them, that they have projects and they can pursue them, it’s fantastic. So I would like to be able to eventually work more on artistic projects, perhaps even my own, when I’m rather older! I did sort of do something like that with the Mosaic Rooms[4], but that a complete coincidence resulting from the fact that for nine months I was not allowed to travel for health reasons. So the Mosaic Rooms became a sort of artistic challenge, and I made it work, I think. But like I said, I really don’t see myself as a spokesperson so much as a catalysing force. That also means that, by the laws of physics, at some stage, I’m going to run out of momentum and ideas!

Still, at the moment, I’m very keen on looking at the next big step in Palestine’s cultural development, which I believe is in need of greater institutionalisation, especially in education and in terms of providing training in the cultural fields. That really has to happen. We have a very serious skills problem in Palestine, and in most of the other Arab countries too.

Maybe Palestine can aim to become a hub for high quality artistic education: that would be brilliant. We did a one-year filmmaking foundation course with the eminent Palestinian filmmaker Michel Khleifi as a pilot scheme in 2004-2006. In many ways, it was very successful because a large number of students went on to work in cinema. Then we had the idea of creating – we were just talking about it with Jack Persekian[5] too – a multi-disciplinary MA programme in filmmaking, but now I’m more and more convinced that we need to start from scratch, to go ‘back to basics’. We may now have just enough competent resources in the country and the diaspora in the cultural fields, and thus ready to start planning for greater investment in cultural education. The National Conservatory of Music has done it. I think we can do something in the visual arts, film, design and architecture too. It is sorely needed. But that’s for the future!

YES: And crafts.

OAQ: And crafts. The idea is that it would be crafts-based.

YES: This is something I noticed, while working on putting on the exhibition on Palestine’s museums. We had to really search for people who knew their craft, who knew about paper, for example, or who knew to work with metal or wood. Where it is not about just furnishing a house but about thinking of the material in order to serve your purpose and express yourself most effectively. It was not easy to find the right interlocutors.

OAQ: I am not at all surprised.

YES: I want to go back to what you said about responsibility (even though after this conversation I really want to consider you as an artist!) When I think about the research I’ve done in Burj al-Shamali and all it has triggered, and the fact that I’m making myself follow up on these different dynamics that have been triggered by the research and by my presence in the camp. In the end, I’m not free either any more, I’m loaded with responsibilities. It would be so easy to say, ‘Well, I’ll just consider the part of the work concerning the images, think about the images, and think about forms to present or not present, how to make them invisible or give their invisibility a presence in some way...’ etc. But the reality is that I have engaged in working processes with older and younger people. Through the work we have done, they were encouraged to look at themselves differently and to dare to try new things, to reach for their dreams. Some of them decided to continue their studies, or they decided to learn languages and go abroad. So today, my endurance is being challenged, I find that I’ve somehow transformed into a kind of micro-institution, trying to ease their presence in a system that is not inviting them to exist in it. Sometimes I even wonder where the limit lies between endurance and self-destruction! I’m thinking about finances constantly, even though I hate to do that - but as you say, it’s a matter of responsibility. What I want to say is that I don’t think we can separate ‘responsibility’ from being an artist; on the contrary, I have the impression that as an artist you have to invent ways to take on the responsibilities no-one else wants to care about.

OAQ: Yes, you have to do that. And I’d say that especially as an artist, you’re always going to have to manage resources, as you must know. I made a decision ten years ago that I would try, though I had absolutely no background in business, to engage with our family business because I wanted to be able to grow the Foundation, and I knew that with our resources we couldn’t do very much more. So it was a challenge, and I’m a Taurus so I very much like challenges! Hamdillah, it worked out ...and now how I extricate myself from that is the key, I don’t know...

YES: I guess it’s good we don’t, this keeps as going and searching for new models…

Thank you for this conversation.

OAQ: You’re welcome!

[1] http://www.qattanfoundation.org/en/young-artist-award

[2] http://www.qattanfoundation.org/en/qcc

[3] http://www.qalandiyainternational.org/exhibitions/introduction-palestinian-museums

[4] http://mosaicrooms.org/

[5] Director of the Palestinian Museum