FILM PROGRAMME

This film programme aims to take viewers on a journey through an archipelago of spatial politics. First, this programme focuses on the information and narratives our spaces, and images of space, project. Through the many filmic forms and styles, we will look at history, design, memory, economics and imagination to unravel layers of politics that sit within natural and built environments. We will also look at how the cinema’s dialogue with landscape, or even the sense of landscape, is used in storytelling, and what that represents in the surrounding context of time and place. Some will dip into cinema’s role in nation formation and national pride, vis-à-vis spatial framings, for example. Including fiction and non-fiction, these films are ethnographic, informative, surreal and epic. More precisely, we will look at how spaces – the finite and the infinite, the imagined and the real – define the human experience and one's right to life, the intention around it and where power sits therein.

CHAPTER 1. LANDSCAPE THEORY

The late 1960s was a time of global politicisation. People everywhere – especially the youth – were becoming increasingly aware of the inequalities in the world. Protest and social movements were rampant against imperial wars of the time in Palestine, Vietnam, Ireland, and elsewhere, as well as grave social injustices, mobilised by civil rights, workers’ rights and women’s rights movements. The ideas of liberation and freedom seeped strongly into the arts, where the avant-garde found space to thrive.

In Japan, people were voicing concerns over a myriad of serious national and foreign policies that included student fees, reallocation of agricultural land, and the continuing American military presence.

At that time, a loose collective of visual artists, writers, musicians and critics inspired by Marxist critical theory, instigated a theoretical discussion around the arts. A group made up of both practitioners and thinkers came to the arts with a focus on its social and political relevance in both substance and presentation. With projects they developed aiming to rethink the liberal value of the works, among the ideas they coined was Fukēi-ron (Landscape Theory). They had begun to notice that the post-war landscape around the country was being built for commercial expansion and urbanisation rather than as a national home for its citizens. This was clearly due to an acceleration in capitalism and an imbalance in political power. Through their images and writings, they presented a view of these landscapes showing how the joint venture between the state and the private sector influenced people’s lives. Their radical critique on the socio-economic failures demonstrated the landscape as economically oppressive and repressively isolating.

The cinema of this theory is largely made up of long static takes of landscapes – urban, rural or otherwise – usually overlaid by a soundtrack of an equally expansive nature, punctuated by silences. We ‘hear’ the narratives through these visceral images, allowing the cinematography to drag the landscapes along. The structure and overbearing silences that the film presents to us match the overbearing architecture of dominance and galloping capitalism that we witness looming within the images. By telling the stories passively, rather than as conventional biographies or crime stories, audiences are invited to notice surrounding contexts. Images of order versus chaos, haves versus have-nots, the employed, the healthy, the content and the inverse. But these images also beg the question of what comes along with noticing these elements of one’s surroundings? What does such a context make one feel? In a time of heightened political frustration and consequent isolation, what drives a person to do in order to be recognised or create meaning in their life? But also what is visibility in such a complex and exasperating world?

The films presented in this section are directed by Masao Adachi and Eric Baudelaire respectively. They were made fifty years apart, in completely different contexts, yet utilising the same elements and addressing issues with a similar mindset. Here we look at civilian murders, but also the political quotidian that surrounded those murderers. While there are other examples of Fukēi-ron, particularly from the formation era of this theory, these films were chosen for their defining position within the school. Adachi’s Serial Killer is considered to be the seminal work that put the theory into film; its use of sound and visuals in particular was a turning point in cinema. This film also lead Adachi and his peers to move on to more actively political engagement with this strain of cinema as can be seen in the following week’s film, Declaration of World War.

The ideas that make up Landscape Theory are as quietly visceral as the images that define it. Today, we see these ideas developed through permeation in other disciplines, and in films from other contexts around the world. Aspects of Landscape Theory – the unseen, the unspoken, the layers of dominance that sit within a given landscape – will permeate this programme.

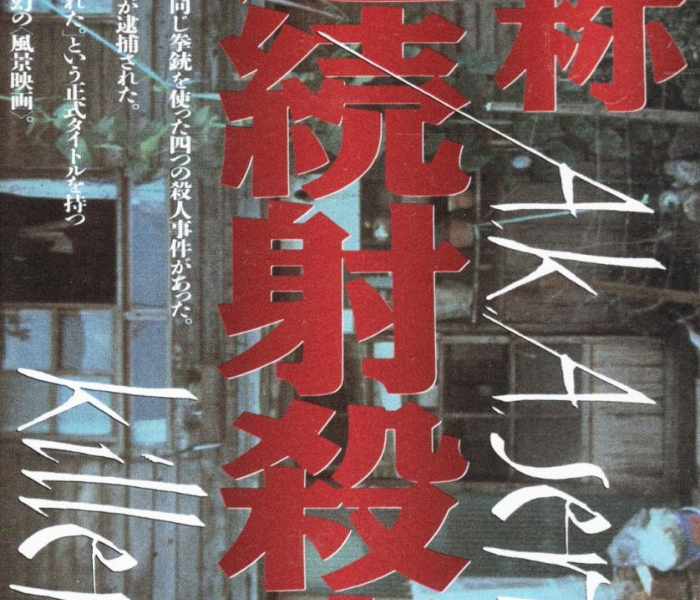

AKA, Serial Killer

The radical documentary AKA: Serial Killer looked at the life of Nor Nagayama, a nineteen year old who killed four people in four different provinces in Japan. In making this film, Adachi did not tell the linear story of Nagayama’s life and crime. Rather, he found that the landscapes that Nagayama came face-to-face with were enough to show the oppression that preceded such a killing spree. Rather than looking at the person at the heart of the story, Adachi looked at the places and spaces that surrounded him. To Adachi, these reflected an imbalance of visibility, where people are unseen and state structures are dominant.

Red Army/PFLP: Declaration of World War

In 1971, on his way back from the Cannes Film Festival, Adachi and his fellow film director, Koji Wakamatsu, also a member of the founding collective, travelled to Lebanon to work with the Japanese Red Army stationed there and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Their idea was to continue the creation of films under this theory, this time with a more international and militant setting. This film was a turning point for Adachi. After this film in 1974, he abandoned cinema and devoted himself to the fight for Palestine. He was imprisoned in Beirut in 1997, and eventually extradited to Japan in 2001, where he continues to make films.

The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years without Images

The political and personal epic of the Japanese Red Army is recounted by Eric Baudelaire as an anabasis, a military journey that is both a wandering towards the unknown and a return toward home. From Tokyo to Beirut amid the post-1968 ideological passions, and from Beirut to Tokyo at the end of the Red Years, the thirty-year trajectory of a radical fringe of the revolutionary left is recounted by two of its protagonists. May Shigenobu, daughter of the founder of the small group, witnessed it closely. Born in secrecy in Lebanon, a clandestine life was all she knew until age 27. But a second life began with her mother’s arrest and her adaptation to a suddenly very public existence. Masao Adachi, the legendary Japanese experimental director, gave up cinema to take up arms with the Japanese Red Army and the Palestinian cause in 1974. For this theorist of Fukēi-ron, filmmakers who filmed the landscape to reveal the ubiquitous structures of power, his twenty-seven years of voluntary exile were without images, since those he filmed in Lebanon were destroyed in three separate instances during the war. It is therefore words, testimony, memory (and false memory) that structure The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi and 27 Years Without Images.

Text from Eric Baudelaire’s website, online at https://baudelaire.net/The-Anabasis-of

For further reading, see Erika Balsom’s text on truth and post-truth in relation to this film, online at https://www.e-flux.com/journal/83/142332/the-reality-based-community/

Also Known As Jihadi

This possible story of a man, Aziz, is told through the landscapes he traversed: the clinic where he was born in the Parisian suburb of Vitry, the neighbourhoods he grew up in, his schools, university and workplaces. And then, his departure to Egypt, Turkey and the road to Aleppo where he joined the ranks of al-Nusra Front in 2012. This journey is tracked by a second storyline, made of extracts from judicial records: police interrogations, wiretaps, surveillance reports. Documents, like pages from a script, are intertwined with images and sounds to compose a film that pertains less to a singular character, Aziz, than to the architectural, political, social and judicial landscapes in which his story unfolds.

This film was part of an exhibition entitled Aprés, which took place in the Pompidou Center in Paris in September 2017. See the project page for more on the project and the ideas it confronts, online at https://baudelaire.net/Apres

REFERENCES AND FURTHER READING: LANDSCAPE THEORY

- Mengna Da, ‘Surveying Landscape for Clues to Political Violence’, Hyperallergic, 14 april 2017, https://hyperallergic.com/372568/surveying-landscapes-for-clues-to-political-violence/

- Becca Voelcker, ‘Landscape Theory in Postwar Japanese Cinema: Fukeiron in Masao Adachi’s A.K.A. Serial Killer’ in Penser l’espace avec le cinéma et la literature, ed. Ludovic Cortade and Guilliaume Soulez (New York: Peter Lang, 2021).

‘We would make a film about how Japan and its landscapes oppressed people. We realised how the landscape reflects the image of society’s power. The landscapes were enough.’ (Adachi). The film is situated in the interval between mounting student and street protests – put down by force in mid-1969 – and armed militancy, in which Adachi took part as a member of the revolutionary Japanese Red Army (Nihon Sekigun).

CHAPTER 2. HOME TO SYRIA

The year 2011 will remain in every Arab’s mind as the year when people went out on the streets to demonstrate their long stifled political voice. Whether in Tunisia, where the head of state was toppled, or in Bahrain, where popular dissent was quashed, the Arab (and greater) world saw a turning point. In Syria, however, what started out as protest brewed into an ongoing war that instigated one of the most sudden displacement crises in modern history. The level of forced migration caused by the various forms of violence posed dire questions to the international community on the right to movement, the right to asylum and the continuous redefinition of these concepts. The meaning of home and safety probed even deeper existential questions on the legal, political, and diplomatic levels. A harsh light was shed on the arbitrary nature of borders and the power dynamics between those escaping war and those who could offer support. Safety, in this case, became a currency for the rest of the world. Care for fellow human beings was seen, not as a duty for nation states to act responsibly to create and offer refuge to those escaping violence, but as tokenistic transactions.

With the formalisation of these questions, a new response had to be created to an entirely new and urgent set of needs. The next set of films address three of the questions of destination and legally afforded safe spaces in the context of the Syrian exodus from war. Presenting completely different filmic styles, we start with an ethnography on design policy by looking at the design and commodification of the individual home. Shelter without Shelter walks us through the policy-making process of institutions, designers, lawmakers and companies who must think of the solutions surrounding relocation of people escaping war. Next, we move from purposed design, to the experimental repurposing of an abandoned space. Central Airport THF is an observational film exploring how a space is perceived and how it can be redefined to serve another purpose than what it was built for. Here we see the successes and the failures of this lived experience in Berlin’s abandoned city airport. And finally, Purple Sea is a tragic, poetic documentary that is set between liquid borders. This abstract and impressionistic essay was shot as people were floating in the water after the biggest boat capsize in the Mediterranean. Co-director Amel Alzakout allows us the space to more seriously consider the powers that play around the lines that create our so-called nation states.

This selection of three films poses the question of what defines ‘home’ both physically and conceptually, what rights we have to it, who decides, and finally, how these decisions, policies and contradictions forever affect people’s lives.

Shelter without Shelter

Shelter without Shelter explores the great hopes and profound challenges of sheltering refugees across Europe and the Middle East since the Syrian civil war began in 2011. Filmed over three years, between 2015 and 2018, this documentary investigates how forced migrants from Syria were sheltered across Europe and the Middle East, ending up in mega-camps, city squats, occupied airports, illegal settlements, requisitioned buildings, flat-pack structures, and enormous architect-designed reception centres. With perspectives from the humanitarians who created these shelters as well as the critics who campaigned against them, the documentary reveals the complex dilemmas and colossal failures involved in attempts to house refugees in emergency conditions. Based on innovative new research at the University of Oxford’s Refugee Studies Centre, Shelter without Shelter offers insights into a universal human experience. We all need shelter, but what is it? First is the question of the purpose-built structures for those who arrived in the mass refugee camps. Shelter without Shelter looks at the policy-making, ensuing commodification of refugee homes and the perceived end experience. Asking the question, what is shelter, the film also questions the process through which decisions are made. While the film does not give much space to those for whom the policies are being developed, it offers a magnified look at the question from the policy-making side of the question. Through the testimonies of those involved we hear the level of calculation involved in the attempt to offer a solution at odds with those who dare to add humanity and warmth. This film presents the value of space as a home and source of dignity and respect, and the impossibility of staunching the problem at its root: violence and displacement.

Central Airport THF

Berlin's historic defunct Tempelhof Airport remains a place of arrivals and departures. Today its massive hangars are used as Germany's largest emergency shelter for asylum seekers, like eighteen-year-old Syrian refugee Ibrahim. As Ibrahim adjusts to his transitory daily life of social services interviews, German lessons and medical exams, he tries to cope with homesickness and the anxiety of whether or not he will gain residency or be deported.

Purple Sea

Since the way to Europe remained blocked for Syrian artist Amel Alzakout, she was pushed to cross the Mediterranean Sea with smugglers. However, halfway to reaching the coast of Lesbos, the boat she was on, carrying 300 people, sank. With a waterproof camera strapped to her wrist, the chaotic events were recorded. The filming, intended to be a documentary of the journey, instead became a record of a tragedy. The muffled images, mostly underwater, of high-colour saturated by the brilliant sun, is the story of an emergency. The sinking took place in the sea somewhere between Turkey and Greece, a no man’s land, and the maritime services of the surrounding states were reluctant to send help. Amel’s poetic narration throughout the film leads us into her thoughts, existential throughout, a stream of consciousness that helped her to survive. She, along with a group of stateless people, is now floating and swimming, caught between the borders, between legalities, with no welcome or entrance pass. Forty-two people lost their lives in this tragedy. The situation begs the question of choice between respect for borders and respect for human life.

See this essay written by Merle Kroger with Amel Alzakout, based on conversations about her experiences leading up to the film, online at https://merlekroeger.de/en/5/purple-sea-essay

For information on the intentions behind and recording the images, and the making of the film, please watch this interview.